Overview of Digestive Pathogens in Pets—Coronavirus

In the previous article, I mentioned the four main causes of digestive health issues in pets due to hot weather. While three of these causes can be mitigated through early intervention or daily precautions, pathogen infections occur invisibly, making them harder to prevent. Therefore, I would like to create a series on common digestive pathogens, aiming to help you gain a clear understanding of these threats. This series may consist of multiple articles, with each one introducing at least one pathogen. In this article, we will focus on one of the most common digestive pathogens in pets—Coronavirus.

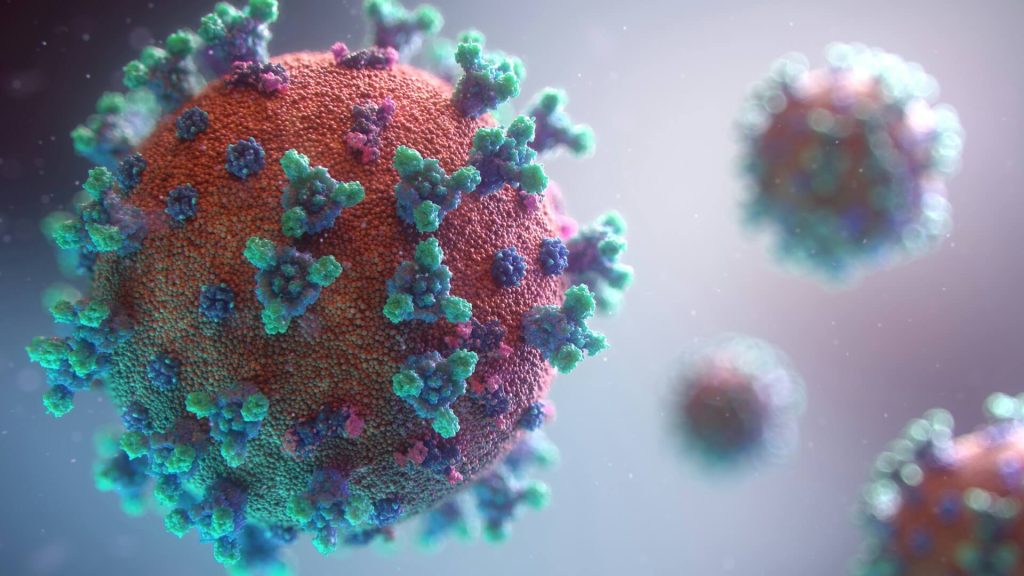

Virus Overview

Coronavirus is a genus in the family Coronaviridae and is classified as a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus. It is round or oval in shape, with a length of 80-120 nm and a width of 75-80 nm. The virus has an envelope, with petal-shaped projections approximately 20 nm long on its surface. These projections can easily detach during freeze-thaw cycles, leading to a loss of infectivity. The nucleocapsid is helical, and the virus has a buoyant density of 1.15-1.16 g/cm³ in CsCL. The virus is sensitive to heat, chloroform, ether, and deoxycholate. It can be inactivated by formaldehyde and ultraviolet light but is resistant to trypsin and acids. The virus can survive in feces for 6-9 days. Coronaviruses only infect vertebrates and are associated with various diseases in both animals and humans.

Clinical Manifestations

The incubation period for pet coronaviruses typically ranges from 1 to 5 days, although this may vary depending on the virus type, pet health status, and individual differences. The primary route of infection is through the digestive tract, mainly via fecal-oral transmission. Healthy pets can become infected by coming into contact with the feces of infected pets or contaminated environments and objects (e.g., kennels, feeding utensils). The virus is more easily transmitted in multi-pet environments. The severity of clinical symptoms can vary, including persistent high fever, respiratory symptoms such as paroxysmal dry cough, wet cough with sputum, and gastrointestinal symptoms like recurrent vomiting and abnormal stools. Coronaviruses can proliferate in various canine and feline cell lines, including primary canine kidney cells, canine thymus and skin fibroma cells, and feline lung cells. Additionally, coronaviruses are sensitive to heat, lipid solvents, nonionic detergents, formaldehyde, and oxidizing agents, but stable in acidic conditions and can be preserved for years under specific conditions.

Coronaviruses detected in cats are generally referred to as feline coronaviruses (FCoV), while those detected in dogs are known as canine coronaviruses (CCV).

Feline Coronavirus (FCoV):

For cats, this virus exists in two forms: Feline Enteric Coronavirus (FECV) and Feline Infectious Peritonitis Virus (FIPV). FIPV typically arises from mutations in FECV, and the diseases caused by these two types differ significantly. FECV generally causes diarrhea and vomiting, posing little threat to cats. However, FIPV, commonly known as feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), has a much higher fatality rate compared to its precursor. Although FIPV’s clinical symptoms predominantly involve the digestive system, it often progresses from isolated digestive symptoms to multi-system involvement.

FIPV can be further divided into two forms: dry FIP and wet FIP. The most prominent feature of wet FIP is abdominal distension with fluid accumulation. Male cats may exhibit enlarged testes, along with fever, lethargy, loss of appetite, and weight loss. In kittens, it may also lead to stunted growth. Some cats may experience difficulty breathing due to fluid accumulation in the pericardium or abdominal cavity. Approximately one-fourth of cats diagnosed with FIP are diagnosed with dry FIP, primarily manifesting as eye inflammation, iris abnormalities, diarrhea, jaundice, and seizures.

Canine Coronavirus (CCV):

In puppies, the mortality rate is relatively high, with a case fatality rate exceeding 50%. For adult dogs, the risk is not as severe, with the primary concern being gastroenteritis.

Virus Diagnosis

Ordinary Coronavirus (FCoV and CCV) Diagnosis: For adult dogs, supportive symptomatic treatment is usually sufficient, while puppies require antiviral therapy. Given that many pathogens can cause digestive issues with similar clinical symptoms, it is recommended to use qPCR for initial screening and then confirm the diagnosis based on clinical symptoms.

FIPV Diagnosis: Early FIPV diagnosis is generally made through comprehensive judgment, such as the presence of pleural effusion, biochemical examination of protein content (which is typically high in FIPV infections, usually greater than 3.5 g/dL), and cytological examination (increased multinucleated leukocytes). While these diagnostic methods can generally confirm FIPV, they may not precisely distinguish between coronavirus and FIP in the early stages. Currently, qPCR can be used for accurate detection. If FIPV is detected as positive in ascitic fluid, it can be almost definitively diagnosed.

Treatment Recommendations

Ordinary Coronavirus (FCoV and CCV): Treatment mainly includes symptomatic treatment, antiviral therapy, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory treatment, and infusion therapy. For adult dogs, supportive symptomatic treatment is usually sufficient, while puppies require antiviral therapy.

Symptomatic Treatment: This includes antiemetic, rehydration, and antidiarrheal measures. For pets experiencing vomiting and diarrhea, intravenous electrolyte solutions are necessary to prevent dehydration caused by excessive vomiting and diarrhea. If symptoms are severe, antiemetic and antidiarrheal treatments, such as antiemetic injections and physical antidiarrheal agents, are required.

Antiviral Therapy: Since coronavirus infection is viral, treatment focuses on controlling and eradicating the virus. Clinical treatment usually involves the use of biologics such as hyperimmune serum, interferons, monoclonal antibodies, and medications containing astragalus polysaccharides to prevent rapid viral replication.

Antibacterial and Anti-inflammatory Treatment: Coronavirus can damage the intestinal mucosal barrier, leading to secondary bacterial infections, necessitating the rational use of antibiotics. Additionally, under the guidance of a veterinarian, pets can be given anti-inflammatory and antibacterial medications, such as amoxicillin and cefazolin.

Infusion Therapy: For pets with poor appetite, severe vomiting, and diarrhea, fluid therapy is essential to replenish fluids and energy. Infusions not only restore water and electrolytes but also provide nutrients, preventing nutritional deficiencies caused by prolonged fasting.

Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIPV): Symptomatic treatments can be used, such as oxygen therapy for respiratory difficulties, nutritional supplementation for poor appetite, and psychological support for lethargy. During treatment, cats should be provided with high-nutrition medications and foods, along with vitamin B supplements to boost their immunity and promote recovery. Experimental treatments with drugs like GS-441 have shown promising results but are not yet approved for sale in China. Other treatments, such as interferons and interleukins, can help inhibit viral replication, shorten the disease course, and reduce the mortality rate. Steroidal medications like prednisolone acetate can suppress immune reactions and alleviate inflammation. In severe cases, where cats exhibit significant pleural effusion, ascites, or intestinal obstruction, surgical intervention may be necessary. Surgical methods include pleural or abdominal puncture to drain the fluid or surgery to relieve intestinal obstruction.

Prevention of FIPV

Currently, there is no vaccine or specific medication to prevent or cure FIP, making preventive measures especially important.

Vaccination: The most effective way to prevent FIP is to vaccinate against other diseases to prevent coronavirus mutations. Kittens should receive their first combination vaccine between 8 and 12 weeks of age, followed by subsequent doses every three weeks until the vaccination program is complete. This can effectively prevent FIPV infection.

Enhancing Feline Immunity: Strengthening a cat’s immunity can significantly improve its ability to resist viruses. Therefore, daily efforts should focus on enhancing a cat’s immunity through a balanced diet, regular exercise, and maintaining good hygiene habits.

Reducing Stress: Stress reduction is crucial in daily life, such as avoiding frequent environmental changes, preventing fright, and minimizing excessive stress in cats.

Regular Check-ups: Regular check-ups are an essential measure in preventing feline diseases. Taking your cat to the veterinarian regularly for health examinations, including blood tests, biochemical tests, and qPCR pathogen tests, can help identify health issues early and allow for timely intervention.